Lebanon is a jagged land – a country with lofty mountain peaks, giant rifts between the rich and the poor, and sharply divided sectarian neighborhoods.

But despite its harsh dichotomies, it is a place of many different stories of happiness: until 2011, Lebanon was one of the top vacation destinations for Arab tourists. Here you will find entertainment centers, discos, bars, shopping malls, beaches, ski resorts, historic sites, shisha cafes, and restaurants. While manned tanks park at key intersections, women do their grocery shopping in high heels and full makeup, as if to declare that everything is fine here. We are all fine. Let’s enjoy life and be happy for as long as the peace lasts.

But in this land of jagged contradictions, not everyone finds it easy to pursue happiness. This article covers multiple happiness stories from Syrian refugees who hope to find happiness in Lebanon. Jaimie Eckert interviewed Syrians and asked them about their happiness stories.

Contents

Can Syrian refugees find happiness in Lebanon?

There are perhaps a million and a half Syrian refugees in a nation of only four million nationals. No one is precisely sure how many refugees there are, because the UN stopped counting at about 900,000 while illegals continued streaming over the porous borders by night.

Some Syrians live in refugee camps. These are the unlucky ones – forbidden by the government to add any kind of reinforcement to their tents that might be seen as creating a permanent settlement, and too far from cities to obtain regular employment. Others live in basements, depots, shacks, and divided sublet housing in the larger metro areas. These are also unlucky. Living on $4 per day, they are often forced to choose between sending their children to school or buying life-saving medicine.

They face overwhelming prejudice, with Lebanese nationals casting blame on Syrians for problems in the country’s infrastructure, economy, and society.

Many are residing and working illegally, since they cannot afford the necessary fees to register as a refugee, and they suffer constantly under the fear that someone will ask to see their papers.

Beneath the weight of their manifold struggles, Syrians in Lebanon learn to cope. But in this land of elusive happiness – formerly known as the “Paris of the Middle East” – can Syrian refugees ever hope to be happy?

1. Yamen’s happiness story

The first Syrian I interview is Yamen, a slender 20-year-old with worried eyes. On the scale of luck – if there is such a thing – Yamen is the luckiest Syrian refugee I know. After fleeing to Lebanon eight years ago, his middle-class family found themselves in a Beirut slum with nothing to their name.

But Yamen’s happiness story reads like a classic rags-to-riches tale, the American archetype of “if you work hard enough, you can do anything.” He learned English almost entirely by himself, and with the help of a nonprofit school for refugee children, studied hard and passed his GED. He began volunteering in the same nonprofit school and developed a reputation as a helpful, reliable worker. A donor chose to sponsor him to go to college.

I meet him on the university campus where he is a premed freshman. Unlike college freshmen in the west, Yamen doesn’t have a car, a hallowed altar of gaming consoles, or lists of upcoming frat parties. After classes, he hails a service, a trundling hop-on-hop-off taxi, and heads back to his poverty-stricken refugee community in Beirut. The Oscar-nominated movie Caphernaum was largely filmed in the same neighborhood where Yamen lives – a place of decay and hopelessness, not happiness. In the schizophrenia of passing back and forth between one of Beirut’s sparkling college campuses and an inner-city slum, I ask him how he finds happiness.

What happiness means to Yamen

“Happiness is about how you’re raised to view things,” he tells me.

“When we were in Syria, we were middle class – maybe lower middle class. But our parents raised us to believe that we have everything, even though we had less than others. We were so happy. They taught us to be satisfied, because happiness is what we have now, not what we might have later.” He explained that this mindset has carried over into their times of crisis. They try to focus on what they do have, not on what they could or might have.

Happiness is what we have now, not what we might have later.

The tricky part of the abundance mentality is that it’s never entirely possible to exclude thoughts about the future. Psychologists have described two kinds of well-being we crave: hedonic well-being, a sense of happiness, and eudemonic well-being, a sense of purpose. Despite Yamen’s carefully cultivated ability to be happy with less, he is still bothered by uncertainty about the future. Syrians who entered Lebanon as refugees entered a state of suspended existence – unable to go back, unable to stay permanently, and unable to secure passage to another country.

Waiting on happiness

He describes the harrowing years of insecurity he and his family endured while waiting for life to begin again. Like all young Syrian men, he knows that stepping foot over the border to his homeland means immediate military conscription – and the odds for ever getting out of the army in one piece are negligible. For Yamen, going back isn’t an option. But staying in Lebanon isn’t easy, either.

I ask him if he has experienced prejudice because of his Syrian nationality. “A lot,” he says. “When they find out you are Syrian, they stop talking to you, because they think we are the main cause of all their problems.”

Having arrived in Lebanon at age 12, Yamen was more adaptable than adult refugees, and quickly learned how to speak the Lebanese Arabic dialect. It is only slightly different from the Syrian dialect, but dissimilar enough to identify one’s nationality. Yamen discovered that by changing his speech, he could hide behind a Lebanese persona and avoid much of the hate that has been directed towards Syrian refugees in Lebanon, especially since the economic downturn of 2017.

Looking both ways, Yamen leans forward in confidentiality. “Thank God the first person here who got Corona Virus was Lebanese and not Syrian,” he says. “So at least they can’t blame that on us, too!”

Thank God the first person here who got Corona Virus was Lebanese and not Syrian, so at least they can’t blame that on us, too!

Then he tells me some spectacular news – but in an odd way. His worried eyes don’t light up when he tells me that the UN has chosen his family to travel to New Zealand.

“Aren’t you happy?” I ask.

“I am. I’m very happy to travel to New Zealand. But there’s also some unhappiness about it, because there’s so much anxiety about when we will travel. The UN told us three years ago that we will be transferred. I feel like refugees need a psychologist just to deal with the waiting process.”

I feel like refugees need a psychologist just to deal with the waiting process.

So Yamen, trapped in suspended existence, tries to keep busy. To block out the ever-present stress of daily life, he writes poetry, some of which has already won awards. He works on his autobiography, telling about life since the war began. He lies awake at night and creates hypothetical scenarios, as if trying to prepare himself for any events he might encounter once life begins again.

Yamen has many reasons to be happy – but the shadow of anxiety in his eyes reminds me that nothing can poison happiness more than the uncertainty that comes from not having a decent measure of control over the future.

2. The happiness story of a Syrian family

Next, I visit a family of four near Jounieh, north of Beirut. Jounieh is Lebanon’s party city, a crowded strip of casinos, nightclubs, and bars. On the north side of Jounieh is Maameltein, the nation’s red-light district. On the east side, atop a picturesque mountaintop, an 8-meter tall statue of the Virgin Mary stands with hands outstretched as if blessing Lebanon’s Vegas strip.

Rajeb and Lulu recently relocated to the south side of Jounieh, where they found a sublet apartment divided in half with makeshift plywood walls. Their neighbors – also Syrian refugees – have the bathrooms and bedrooms, while they have the kitchen and living room. For this arrangement, they pay $250 per month. Each day, Rajeb rides his motorbike to Beirut in search of day labor. Somehow, they survive. Their daughters, 16-year-old Bushra and 7-year-old Ghazal, used to attend a free refugee school in Beirut, but rent in Beirut cost twice as much. Relocation to Jounieh means no more school.

Each day, Rajeb rides his motorbike to Beirut in search of day labor. Somehow, they survive.

Bouncy, 7-year old Ghazal beams up at me with unaffected joy, apparently unaware of the long-term effects of dropping out of the first grade.

What happiness means to 7-year old Ghazal

I ask Ghazal about happiness.

For me, happiness is that one day we will have a big palace with a pool. And I’ll have a cat, and an iPhone, and my own bedroom.

She giggles and turns back to watching Disney’s Arabic- dubbed Snow White on the family’s crackly television. Despite desperate times, her parents have shielded her carefully from the realities of refugee life, that the sacred innocence of childhood might be preserved a bit longer. Unlike Yamen, no worry clouds her little eyes. Perhaps in a few years, things will be different.

Finding happiness in difficult times

Cheerful, 16-year-old Bushra, in the first flush of womanhood, likewise doesn’t seem to comprehend the full weight of their situation. She is bothered at having to quit school but appears to be as happy as her western counterparts, minus the teenage angst and alienation from adults. She wears a big cute bow in her hair and treats her parents more like her best friends than authority figures.

Bushra blushes as her mother tells me about a marriage proposal which they turned down a few weeks ago. I listen to Lulu describe her desire for Bushra to finish school before getting married. Meanwhile, Bushra swipes through TikTok videos, singing along to the English lyrics, even the bawdy ones that would singe her ears if she understood the meaning.

I am struck by how sheltered and innocent she is – at once living in a chaotic, globalized, unfair world, and yet passing blithely by the markers of it, decking herself in bows, bright colors, and social media accounts. Again, I felt that there must have been a measure of intentionality behind such a home atmosphere.

Dealing with unhappiness

“I don’t like to show my girls when I’m unhappy,” Lulu says, her brows furrowing. “When I cry about our situation, I get dizzy and I have nosebleeds. This makes Rajeb and the girls worry about me too much. But it’s very hard to hold it in. I feel like a balloon. I feel like I’m choking, as if someone is putting their hands around my neck and I can’t breathe. But I try to show that everything is ok.”

I feel like I’m choking, as if someone is putting their hands around my neck and I can’t breathe.

As she says this, her husband enters the room with a tray of Syrian sweets for us, says a few soft words to Lulu, and leaves the house to go buy some bread for lunch. Her tense expression is broken, and she smiles once more.

I can’t help but tease her about how cute they are together. This couple, whom I have known for years, are the ones who have convinced me that arranged marriages can work very well. Too traditional to kiss or touch in public, they nevertheless make each other laugh constantly and look at each other with soft, kind eyes. When Lulu says she doesn’t like to make Rajeb worry about her, I have no doubt that her efforts to contain her unhappiness are an act of true love.

“I try to do something every day to be happy,” she says. “I don’t just sit around – I get up, I dance, I clean the house, I play with my children, I study English, I read the Qur’an. I can’t just sit and do nothing.”

Hoping for happiness

“You know what really makes us happy?” Bushra asks, a mischievous sparkle in her eyes. “Let me show you what we do when we’re starting to feel sad.” Lulu and Bushra hop to their feet, take each other’s hands, and start jumping up and down. “We’re going to Canada! We’re going to Canada!” They exclaim, goofy grins on their faces. Little Ghazal claps her hands gleefully at the pretend game, as if the tickets were already in-hand. If wishful thinking could create reality, Lulu would already be on a plane. Unfortunately, there’s no hint of legal emigration anywhere in sight. But this hasn’t stopped Lulu from idolizing the nation which has taken so many Syrian refugees.

“I know the history of Canada’s flag, I know all ten districts and where they speak which language,” she tells me. “I even know the national anthem already.” In adorably accented English, she belts out the Canadian anthem, her eyes shining. On the wall is a hand-made Canadian flag on a piece of lined school paper.

“It bothers me that we don’t have the right to travel,” she continues. “I’m willing to leave everything behind. I just want the chance to live somewhere safe.” She tells me of her dream to open a restaurant in Canada with her husband. She swears he makes the best falafels and pastries.

Ultimately, this is what keeps them alive: a dream. The whole family longs to go to Canada. It is this goal that comforts them during sadness and gives them a sense of purpose – of happiness, even. As Viktor Frankl admitted that one can find meaning in the contemplation of his beloved, it seems that one can also find happiness in the contemplation of his dreams, no matter how far out of reach they may be.

Lulu finds her happiness in creating a protected world for her girls to grow up in, believing that things will only get better.

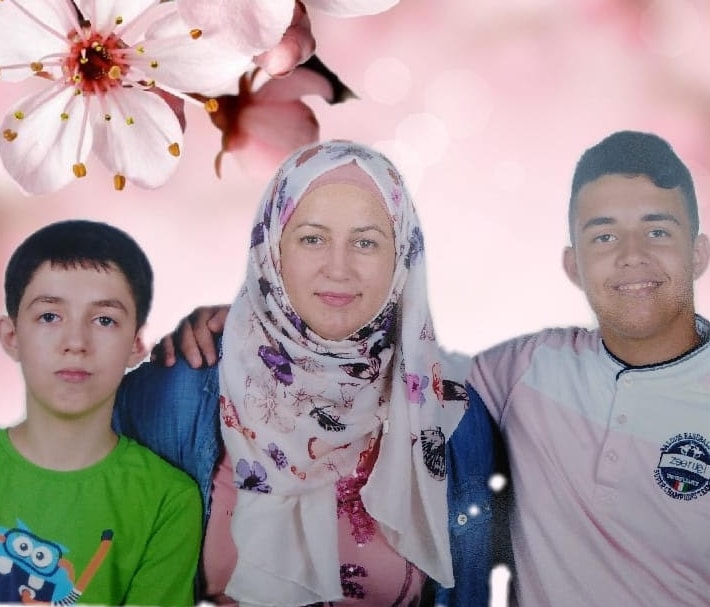

3. Fatima’s happiness story as a Syrian refugee

My last interview was with Fatima, a feisty half-Hungarian, half-Syrian refugee with a big heart for underprivileged communities.

Long ago, her mother, a Hungarian, married a handsome Syrian exchange student at her university. After graduation, they returned to Syria together, building a wonderful life in times of peace. Fatima’s mother loved Syria and her new extended family, and never felt the importance of providing a European passport for any of her children. Her sons and daughters – including Fatima – grew up as Syrians in Syria.

Then the war struck.

Finding happiness during times of war

Fatima was at home with her two young sons when a bomb hit their building. Her youngest son, Ahmad, was near the explosion. He experienced such a strong shock that he didn’t speak for the next two years. They decided it was time to leave Syria.

Unlike most Syrian women, Fatima didn’t just stay home and let her husband provide for the family. She hustled. Hunting up work here and there, she was determined to provide a future for her sons. Sometimes she only earned $2 per hour. Sometimes she worked at schools, receiving no salary except her son’s enrollment. She learned English through free classes at Caritas and has now been working for the past four years at a nonprofit organization that helps Syrian refugees.

“I don’t like to think about problems,” she says resolutely. “There is no future in Syria if we go back, and the situation here in Lebanon is hard for us. I’m working long hours and sometimes I cannot see my children and take care of them, but I’m trying to find a way to give my kids a good life.”

Her rule of life is to put her nose to the grind and work rather than worry. After a long, arduous process, she received Hungarian citizenship for her and both her sons. Technically, she can travel to Europe anytime she wants – but is paralyzed by fear. She cannot speak Hungarian, she knows no one, and is unsure of how she will obtain a job.

How Fatima deals with feelings of unhappiness

I ask her about how she deals with feelings of unhappiness. After all, no one can outrun unhappiness, no matter how hard they work. She responds with candor.

“When I have bad days, I always say to myself, ‘Be strong! Be strong! Your kids need you. You should be strong, you are a strong woman!” A moment later, though, she admits that what helps her the most is to pray.

In a culture where religion and society are practically inseparable, many refugees find a call to devotion in the midst of their crises. But Fatima’s devotion is a different hue than most. Typically, Syrian refugees find relief in the idea that all things in life – good, bad, mundane, and dramatic – are willed by God. The Orientalist Raphael Patai writes that the Islamic belief in qadar – the divine decrees – is a major source of resilience for Muslims. Although he warns that divine fatalism can have a retarding effect on positive growth during good times, he recognizes its enormous strength during the bad times:

When misfortune strikes, [belief in the divine decrees] is an inestimable asset: it imparts to people the ability to bear with equanimity the hardest blows of fate, since everything that happens to man is the will of God.

Finding happiness in religion and faith

Unlike many Syrian refugees, however, Fatima’s devotion is not merely a leaning into the unquestionable divine will. Raised by a Muslim father and a Catholic mother (who later converted to Islam), she then worked for a number of years with Evangelical aid agencies in Lebanon, all of which have given her the ability to step back and appreciate multiple religious views.

“My picture of God started to be so different,” she says. “I like so much this sentence, ‘God is love.’

Before I came here, most parents used to teach their kids that if you don’t do this or that, you will go to hell. This is not true, I discovered that God loves us and gives us chances and opens doors when we come to Him.” As she speaks, I hear a tone of resilience. Apparently, the strength to bear up under difficulty takes many forms. She clings to the hope of an open door.

Fatima’s true happiness story

I ask her what would give her true happiness. “For me,” she says, “I want freedom. I don’t like Arab countries, because they control women.

I want freedom for myself, I want to be a real woman. I want to show others in the world around me who I am. I don’t want to cover myself and hide my personality. I want to share the things I know with others.” She tells me how deeply she values education, and her dream to see her sons graduate. “Also, I have a dream for myself,” she says. “I couldn’t do it in my country, but I want to study to become a social worker or a news broadcaster to talk about problems in communities that need solutions.”

For a plucky, no-nonsense woman like Fatima, happiness is constant growth. It is sharing with others the good things that she has and knows. It is to see her sons rooted and growing. It is, at the end of the day, far less about material things as it is about meaningful goals and self-actualization.

What you can learn from these happiness stories

When I began interviewing Syrians in Lebanon, I wanted to know how refugees find happiness. What I discovered was a crooked path of already-but-not-quite. Perhaps my findings can be summarized by the adage that every cloud has a silver lining, but every silver lining has a cloud.

Refugees do experience happiness to a degree. Just because they have experienced extreme loss does not mean they stop dancing, singing, gathering for celebrations, loving, marrying, pursuing education, and searching for meaningful goals. These are all things they link to happiness, and they pursue them with gusto.

At the same time, the path to happiness is far more convoluted for Syrians than it is for others, because they lack a sense of control over their circumstances. In most cases, their lack of control is real, not perceived. At any moment, they could be beaten on the streets because of their nationality or deported to Syria. They may or may not have food to eat on a consistent basis.

For them, the greatest blow to their sense of happiness isn’t the fact that they must work harder and live in substandard housing. The real damage comes from this state of living in suspended existence, ever unsure and uncertain about what the future holds. Uncertainty and lack of control characterize each of the dozens and dozens of stories that I have heard during my years working with Syrian refugees.

Closing words

What Syrian refugees can teach us is the value of seeking happiness even within uncertain environments. There will be legitimate moments when we lack control over our environment or the things happening to us. Without denying the destructive effects this can have, it is possible to seek the silver lining in every cloud.

- Like Yamen, we can educate ourselves.

- Like Lulu and Rajeb, we can preserve our children’s youthful innocence and belief in a good world.

- Like Fatima, we can hustle.

Because for each of them, these small but significant actions are a vote of confidence in the existence of happiness. They may not have it in its entirety, but they know it exists, and they believe that someday, it will be theirs again.

Since 2013, Jaimie Eckert has lived and worked in Beirut, primarily in the nonprofit sector. She is currently pursuing a PhD in Intercultural Studies and writes about finding meaning in life at her website scrupulosity.com.