I was on the train recently in Amsterdam and made the mistake of looking around at my surroundings. I know, it’s a blatant violation of the “mind your business” ethos perfected by us Dutchies generally and subway riders in particular.

People looked miserable. Those who were engaged with their phones looked forlorn, and those unfortunate souls who forgot to charge their phones the night before looked positively suicidal. I took notice of my own expression and I was no exception. I looked like I’d just lost my dog.

But then something interesting happened. A South-Asian couple got on the train. Clearly in love, and clearly deeply happy, this couple wore faces of contentment. And shortly thereafter, I noticed a few of the people around me stealing glances at the couple, their lips curling up ever so slightly. One would never have mistaken them for uproariously ecstatic, but they were definitely happier than they’d been a moment ago. Even I started to smile.

It made me wonder, is happiness contagious? While I’d love to say that my fleeting, anecdotal experience was enough for me to answer the question with an enthusiastic yes, I’m afraid that I was compelled to do some actual research.

What I found was intriguing.

Contents

Does science think that happiness is contagious?

Given how central happiness is to all of our lived experiences, it’s somewhat surprising that research into the topic is much less abundant than research into, say, crippling depression. However, there have been a few attempts to determine the virality of happiness.

One of the most extensive studies occurred in 2008. Using cluster analysis (a methodology used to, well, analyze clusters), the researchers were able to identify clusters or groups of happy people in a large social network (the real kind, not Facebook).

The authors found that “happiness is not merely a function of individual experience or individual choice but is also a property of groups of people.”

Now, I should note that this finding doesn’t necessarily mean that happy people are causing the people around them to become happy. What could be happening is that happy people seek out other happy people and exclude unhappy people from their social networks.

But one of the most interesting parts of Dr. Christakis’ study was the longitudinal aspect. The good doctor found that those people who were at the center of these happiness clusters were predictably happy for years at a time, suggesting that observing happiness can at least keep one happy for an extended period of time.

Can happy content spread happiness?

What about online, where we all seem to spend most of our time anyway? At times, Facebook can seem like a giant echo chamber of negativity and paranoia. Does the inverse hold true? Can happiness, once expressed online, ripple through an audience and go viral? It turns out that it might.

Happy content is more likely to spread online than unhappy content so we’re more likely to run into the former than the latter (although if you’re anything like me, it can sometimes seem like just the opposite). Jonah Berger and Katherine Milkman of the University of Pennsylvania examined thousands of New York Times articles published online and found that the positive ones were emailed to friends far more frequently than the negative ones.

Actually, the findings were more complicated than that. The frequency of sharing depended not just on the positivity or negativity of the emotional content of the material, but also on how stimulating the material was. Content that provoked feelings like awe, anger, lust, and excitement was more likely to be shared than content that depressed emotion (like sad or relaxing content).

I should note that all of this research is complicated by the fact that the meaning of the word happiness isn’t universally agreed upon. A quick glance at this Wikipedia article on the philosophy of happiness demonstrates the variety of opinion on this issue. As a result, researchers have trouble agreeing on what constitutes “true” happiness and how to measure it. While people can simply be asked, “How happy do you feel generally?” or “Are you happy right now?” those questions may mean different things to different people.

A personal example of contagious (un)happiness at work

Early in my career, I worked in an office in a remote location in northern Canada. My two closest friends in the office were a pair of miserable young men who were both very unhappy with the location we worked in. Both of them wanted to return closer to home which, for them, was thousands of kilometers away on the east coast.

On a nightly basis, we exchanged stories over drinks at the local bar about how sad we were and how much we wanted to get out of that town. This was the worst thing I could have done. Rather than seek out the more positive and happy influences in our office, I surrounded myself with sad sacks and became a sad sack myself.

If happiness is contagious, then what about sadness?

Some of this research left me with more questions than when I started. For example, we’re all familiar with the phrase “misery loves company.” But is it actually true? If happiness clusters in large social networks, does misery and sadness do the same?

Or what happens when a miserable person is thrust into a happy milieu? Do they become happy all of a sudden? This article that examines the link between happy places and high suicide rates suggest that no, maybe not. They might just get more miserable. Perhaps fatally so.

Can you make happiness contagious yourself?

So what can you do to take advantage of these findings?

- First, surround yourself with happy people! While they might occasionally be annoying (think of the assistant at your office who’s always chipper no matter how early it is), the amount of happiness regularly around you is one of the best predictors of how happy you’ll be for years to come. Not only will you feel better, but the effect could also be a feedback loop, as your happiness attracts other happy people, which makes you happier, which attracts more happy people until eventually, you’re so giddy your jaw freezes from smiling so much (okay, maybe I’m exaggerating now).

- Second, keep the negative Nathans and Nancys at bay. If my experience in that sad office in northern Canada is any indication, surrounding yourself with sad individuals is the fastest way to become sad yourself. This is not to say that if you encounter someone who’s clearly unhappy, or even depressed, you shouldn’t try to help them. Indeed, trying to help is the only human thing to do in that situation.

- Third, intentionally seek out positive and uplifting content to consume. There’s nothing worse for long-term happiness than spending all of your time reading and watching people being nasty to and about other people. This should be easy since, as discussed above, uplifting content spreads farther and faster than downer articles and clips.

- Fourth, try to be clear in your own mind about what happiness means to you. It will be difficult to achieve true happiness if you’re constantly on the fence about that term actually means.

- Lastly, be a part of the solution rather than the problem. Unlike my behavior in the aforementioned subway, where I sat silently and stared miserably, be like the happy couple that set off a chain reaction of smiles. In other words, put happiness out into the world and allow it to spread.

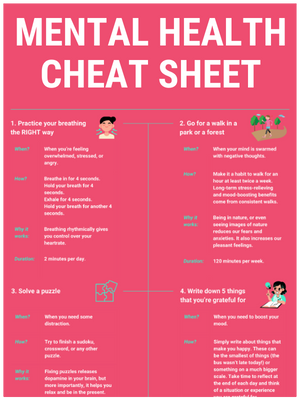

💡 By the way: If you want to start feeling better and more productive, I’ve condensed the information of 100’s of our articles into a 10-step mental health cheat sheet here. 👇

This Cheat Sheet Will Help You Be Happier and More Productive

Thrive under stress and crush your goals with these 10 unique tips for your mental health.

Wrapping up

Okay, I’ll shut up in just a moment. But let’s go over what we’ve learned:

- Happiness might be contagious.

- Whether happiness is or isn’t contagious, happy people seek out other happy people.

- Happy people keep the people around them happy for longer than they would be happy otherwise.

- Happy content spreads farther and faster online than unhappy content, so you’ve got no excuse to sit around all day watching that episode of Futurama where Fry’s dog dies.

- Sad people make me sad. I don’t have the data to turn this into more generalizable advice but, for what it’s worth, I suggest you keep your exposure to miserable folks to a minimum.

- The meaning of happiness is up for debate. It could mean one thing to you, another thing to your neighbor, and a third thing to your spouse. As a result, it’s hard to measure scientifically and accurately and may account for the lack of research on this particular topic.

Hopefully, I’ve helped to shine a little bit of light on the question you came here to have answered. Maybe learning the answer even gave you a little bit of happiness. Now go spread it around. ?